This article contains opinions about the points list that are solely those of the writer, Cyclopes8. These views do not reflect the personal stances of any members of the Canadian Highlander council, nor do they reflect the stances of the council itself.

Contents

- Introduction

- What is Opportunity Cost?

- Opportunity Cost and the 1 Point Barrier

- Benefit: More Ways to Regulate Decks

- Benefit: Removing the Ability to “Free Roll” a Card

- Potential Benefit: More Choices for Point Spreads

- Drawback: Soft Banning

- Drawback: Weakening a Deck Too Much

- Potential Drawback: Splash Damage

- Conclusion

Introduction

This article is meant to cover a small portion of the factors that influence the decision to move a card onto the points list. In this article, the points list will be explored through the lens of opportunity cost. Pointing cards is a very nuanced and difficult decision, and trying to cover all aspects that are considered when pointing a card is beyond the scope of this article.

First, we will discuss the concept of opportunity cost and how it applies differently to pointed cards and unpointed cards. Then, some benefits and drawbacks to 1 point cards will be discussed. This article is not intended to be a guideline to the characteristics of a pointed card or to state why certain cards are currently pointed or unpointed but rather to provide a more broad view of why pointing cards is difficult and how pointing cards can affect the format.

What is Opportunity Cost?

The phrase “opportunity cost” comes from economics and describes the loss of potential gain from other alternatives when one alternative is chosen. To put it more plainly, opportunity cost is what you “give up” by making one choice compared to your other options.

If you could only choose one, which would you choose? What are you giving up?

In Magic terms, consider the choice between including Lightning Bolt, Llanowar Elves, or Duress as a 1 drop in your deck. Lightning Bolt is a removal spell with high flexibility that has a good fail state of always being able to damage your opponent directly, allowing it to be played at most points of the game. Llanowar Elves is great in the early game to accelerate your mana, but it is often a poor card to draw later in the game when the extra mana is no longer necessary. Duress gives you a lot of agency and ability to interact with problematic noncreature cards by taking them out of your opponent’s hands, but there are matchups where it may not be useful because you need to deal with creatures, and it is usually terrible to draw later in the game as hands are empty. Which do you choose?

If you choose Lightning Bolt for this slot, you gain flexible removal, but your opportunity cost is early game acceleration or the ability to interact early against archetypes like combo or control. If you choose Llanowar Elves, you gain proactive acceleration, but your opportunity cost comes in the form of losing out on interaction. If you choose Duress, you gain the ability to interact with your opponent’s hand, but your opportunity cost is early game board interaction or development. Each choice has benefits, but it also has a hidden cost associated with the cards that get excluded in its place.

This example is simplistic on purpose but demonstrates the idea behind opportunity cost. This concept is important because it is one of the backbones behind the existence of the points list itself and is a major factor in how 1 point cards affect our format.

Opportunity Cost and the 1 Point Barrier

To understand why it is difficult to get cards onto the points list, let us consider a hypothetical deck building scenario. Suppose the average deck contains about 35 lands, 60 unpointed nonlands, and 5 pointed cards. We will ignore the lands and just look at the 60 unpointed nonlands and the 5 pointed cards. Suppose all cards can be given a rating between 1 and 10, indicating how powerful those cards are in the deck. These numbers do not actually mean anything, and it is not reasonable to give every card an objective numeric rating, but this process will serve for illustration purposes.

The quality of unpointed cards can have large variation in 100 card singleton

Usually, the quality of the nonland cards in the deck varies considerably. While there may be some cards that are 9s or 10s in power, we usually have to settle for much weaker cards due to the singleton nature of our format. Decks may have to include cards that are 3s, 4s, or 5s in power. In this simplified scenario, for a new card to replace one of the currently selected nonlands, it only has to be better than the current worst card in the deck. If the current worst card is a 4, then a new card that is a 5 improves the deck. It is easier for cards to slide into this category because the competition is not too fierce.

Pointed cards are almost always of extremely high quality and impact

Now, consider the options for the 5 pointed cards. Almost always, pointed cards are of extremely high quality and would often be rated as 9s or 10s in power. This means that the bar for a new card to be worth considering is much higher. A strong card that is a 7 or 8 is unlikely to be worth running over a 9 or a 10. The competition for what to select as your points is much higher compared to selecting your unpointed cards.

So far, we have only covered the “bar of quality” aspect of unpointed versus pointed cards. What does this have to do with opportunity cost? The answer comes when looking at the average rating of each group. Averaging consists of adding up all of the ratings of each card and then dividing by the number of cards. Among the 60 unpointed nonlands, the effect of any individual card is muted because the average is divided by 60. For the 5 pointed cards, the effect is divided only by 5. In other words, if you replace a card with rating X from the 60 unpointed cards with a card with rating X – 1, that group “loses” 1/60th of a point (~0.0167). If you replace a rating X card from the 5 pointed cards with a rating X – 1 card, that group “loses” 1/5th of a point (0.2), 12 times the “loss” compared to the unpointed nonlands in this example. This “loss” can be considered the opportunity cost associated with swapping out cards. Losing quality from your pointed cards is more costly than losing quality from your unpointed cards because the slots are more limited.

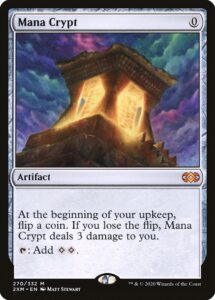

How does a new card measure against Recall, Crypt, Tinker, or any other card on the points list?

It would be reasonable to ask, “Why is this relevant to cards going from 0 points to 1 point?” The reason is that comparing pointed cards to unpointed cards often shows a stark contrast in quality. Very few cards live up to the quality of cards that make it on to the points list. A card that is among the best unpointed cards might rate as an 8, but that does not necessarily make it strong enough to be worth choosing as a pointed card. In theory, the point list could be expanded to include “worse” cards, but no matter how far down you expand the points list to include the 7s and 8s, as long as the points list includes 10s, the opportunity cost of not choosing those 10s is high.

If you have ever heard or read the phrase, “This card is not strong enough to be pointed,” odds are that it can be viewed as, “This card is strong but not so strong as to make up for the cost of giving up on even stronger already pointed cards.” Cards simply do not exist without context, and in the context of the points list, as soon as a card crosses the barrier from 0 points to 1 point, it has to contend with everything else on the points list. With the points list containing incredible design mistakes such as Moxen, Black Lotus, or Ancestral Recall, or even smaller pointed cards such as Treasure Cruise or Ancient Tomb, it can be difficult to measure up.

Now that we have covered one of the main difficulties preventing cards from being added to the points list, it is time to cover some of the benefits and drawbacks of 1 point cards.

Benefit: More Ways to Regulate Decks

Points lists or ban lists can be thought of as ways to regulate the strength of decks directly from a format level. One of the beauties of a points list compared to a ban list is that this regulation can be more nuanced and gradual compared to the binary banned/not banned state offered by a ban list. Pointing cards offers a way to softly power down decks rather than remove them from the format outright.

When considering a specific deck, think of each of the pointed cards that the deck is interested in as a tool for regulation. If a deck is interested in very few pointed cards, there are not many tools on the points list to regulate that deck. This can cause issues where a small set of cards are responsible for much of the burden of regulating that deck. This can make it difficult to make changes to curb the power of a deck without highly inflating the points value of specific cards. Let’s consider three separate decks: an Ancestral Recall control deck, a triple Moxen aggro deck, and a Time Vault combo deck.

Ancestral Recall is currently 8 points and shoulders most of the burden for blue decks

Ancestral Recall is currently the highest pointed card on the list at 8 points. This provides very little room for Recall players to choose other options for their points, even though there are many that are worth considering depending on color combination. Suppose that Recall blue decks were considered a problem. One alternative is to place more regulatory power on Recall by raising it to 9. This option has a few problems, but the most important one is that there is a ceiling on how high a card is allowed to go. If Recall goes to 9 and Recall decks are still a problem, what do you do? Raise Recall to 10? There are really only two outcomes: either Recall is abandoned by the player base for having too high of an opportunity cost to run because you lose out on all of the other pointed cards, or Recall becomes the only pointed card in a list because it is deemed that the opportunity cost of giving up the other cards is lower than giving up on Recall.

Instead, if it is possible to identify more cards that the Recall decks want, more 1 point cards could be added to the list. This alleviates the pressure put on Recall itself to regulate the Recall decks. In fact, with more 1 point cards that the Recall decks are interested in, the opportunity cost of Recall rises and could, in theory, make it less necessary for Recall to be 8 points.

Moxen are 3 points and need to stay the same point value

Triple Moxen was a common spread for many aggro or midrange decks prior to the 2025 start of year update. For a long time, there were very few pointed cards that these decks were actually interested in, and so most of the regulation of these decks was carried by the Moxen themselves. In effect, the opportunity cost of choosing Moxen was so low as to be close to zero. If these decks need to be reigned in, one option would be to increase the value of a Mox. However, it is awkward if any Mox is worth more points than any of the others, so an increase to one Mox almost requires that the other Moxen are raised to match. That means that raising the Moxen effectively entails a 2 or even 3 point increase. This solution is too dramatic and is not granular enough.

With more 1 point cards that these decks care about, there is more pressure on what can be used for the last point, increasing the opportunity cost of selecting any individual last point. If there are enough 1 point cards, then the Moxen themselves have a large opportunity cost, which may cause players to “break” one of their Moxen into more 1 pointers. More levers makes the burden of regulating the deck by moderately pointed cards lower and can lead to more subtle and controlled changes.

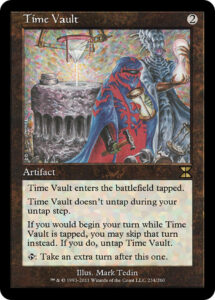

Time Vault is 7 points, and like in many combo decks, the combo pieces are irreplaceable

Finally, let’s look at a combo deck such as Time Vault. Time Vault is irreplaceable. The deck has to pay for Time Vault or else it no longer is the same deck. Placing much of the regulatory power of the deck on the namesake card is intuitive and reasonable. If you want to weaken the deck, forcing the deck to pay more for its required card is simple enough; however, the viability of many combo decks in the format heavily lies in their access to effects such as tutors or fast mana, many of which are pointed. In effect, because the points for Time Vault are locked in, the opportunity cost falls on the non-Time Vault cards they have access to.

If Time Vault needed to be weakened, raising Time Vault to 8 is a viable plan, but instead it could be more beneficial to raise the opportunity cost on the other 1 pointers that Time Vault plays by making more of the effects that they want pointed. This weakens the deck by making the choice of 1 pointers harder rather than simply restricting those choices further.

Benefit: Removing the Ability to “Free Roll” a Card

One potential benefit to adding a card to the points list is to remove the ability for decks to “free roll” that card. This phrasing is a little bit misleading, as no card is truly “free” from opportunity cost, but it is true that the cost of including an unpointed card is far lower than a pointed one. Removing the ability for a deck to free roll a card creates a much different deck building experience than simply raising the point value of an already pointed card. Let us consider the card The One Ring (TOR) in the context of a deck such as Paradox Academy.

The One Ring is currently unpointed, so all versions of decks have the chance to include it

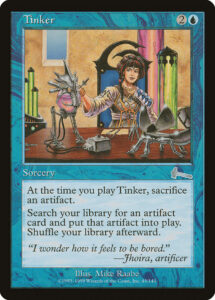

Paradox Academy is one of the best users of TOR in the format, as it has access to large amounts of acceleration to get TOR out early and has several ways to untap it, such as Minamo, School at Water’s Edge, the namesake Paradox Engine, or cards such as Voltaic Key. Suppose that Paradox Academy was considered too powerful of a deck, and we wished to reduce its power.

In one scenario, we could increase a card that Paradox Academy already plays. Perhaps Tinker from 3 to 4, or Academy from 1 to 2 would suffice. No matter what we change, if we only look at currently pointed cards, every version of Paradox Academy gets to play TOR. The opportunity cost of including TOR while it is 0 points is close to zero, given its strength within the deck. Every version of Paradox Academy is weaker but still has access to TOR.

Instead, if TOR were to be pointed, a split is created. Now, the opportunity cost of including TOR is nonzero and places pressure on other pointed cards within the deck. Some pilots might prefer to cut TOR and keep the rest of their pieces. After all, the deck was still functional before the printing of TOR. However, others might view TOR as too necessary to their game plan and will change their points instead to include TOR. Every version of Paradox Academy is weaker but not all versions have access to TOR.

There is no default better answer. Some effects are fine for decks to have access to unrestricted, while for some effects, a better result might be obtained by putting the card onto the points list. As of the time of this writing, the most recent example added back to the points list was Balance. Balance was good in nearly all combo decks. It becoming pointed did not make it worse in those combo decks, but it forced combo decks to choose whether they wanted to pay the price for it. Some decks chose to keep Balance, but others did not. To produce such a widespread effect across multiple decks without adding a card to the list would have required many individual points changes to touch each deck individually, whereas the solution of putting Balance back onto the list accomplishes a similar effect more elegantly with a single change.

Potential Benefit: More Choices for Points Spreads

Another possible benefit that comes from adding to the points list is the increase in choices and customization of point spreads. This idea has been hinted at earlier in the article, and it is relatively self-evident. Adding to the points list can only give more options for ways to combine them compared to not adding to the points list.

However, it should be noted that this benefit is an outcome and not a goal of the points list. It is not a metric to maximize, because even if there are fewer cards on the points list, there are still all of the other cards in the deck that get to be customized. A card being on or off the points list does not change the ability for the card to be included or excluded, it simply changes the incentives for including or excluding that card. In this sense, the “degree of customization” is somewhat false.

To use an extreme example, suppose the points list consisted of 10 cards each worth 2 points. The number of possible combinations of choices that add up to 10 points is 252 (10 choose 5 using combinatorics, for those who are familiar with probability and counting). If the points list instead consisted of 20 cards each worth 1 point, the possible combinations explode to an incredible 184,756 choices! This result is arbitrary. Nothing about the number of choices available indicates how fun, balanced, or interesting the format is.

In summary, this consequence of more choices is generally a happy result but it is not a metric to be optimized. The points list should be focused on creating an enjoyable experience, a process which can often result in more choices and customization but does not always do so.

Drawback: Soft Banning

A core reason to use a points list rather than a ban list is to allow players to play with any cards they want. The trade off is that players cannot play every card. This philosophy is baked into the format itself. When a card is pointed, there is the possibility that it ends up seeing no play because it is not considered strong enough for any player to include it in their deck. Another way to look at it is that the opportunity cost of giving up other pointed cards is too high to include that card. When this happens, it is common to refer to the card as “soft banned”, as the playrate of the card diminishes to zero as if it were banned.

Library, Twist, and Pod were previously pointed cards that saw little play as the format sped up

A card reaching soft ban status is highly undesirable because it violates one of the core reasons the format has avoided a ban list in the first place. Cards become pointed for a number of reasons, but ultimately, they should still be playable or else the purpose of pointing them in the first place is moot. Generally, pointed cards are stronger than unpointed cards, but if they see no play at 1 point, then that assumption might end up being false. This happens most often for older cards that have been 1 point for a while, but it is a risk with any card added to the points list. Going back to the beginning of this article, a card needs to clear a very high bar to become pointed, and if that card is pointed without clearing that bar, there is a high chance that it can end up in soft ban territory.

Some pointed cards see very little play – are they soft banned or are they just underexplored?

Determining whether a card is soft banned or not can be tricky. Technically speaking, soft banning is a matter of perception, not an objective metric. Any player can choose to include an underplayed pointed card in their deck at the cost of giving up a more common choice. In that sense, cards like True-Name Nemesis or Wishclaw Talisman are perhaps underexplored or overlooked rather than truly soft banned. It could be possible that True-Name Nemesis would become popular if aggro strategies became dominant in the format and that it is simply a matter of the state of the overall metagame that prevents it from seeing play. There is not always a clean solution: some cards end up in soft banned status because they are a bit too powerful at 0 points, but end up not being worth the opportunity cost at 1. It is difficult to be certain why a card does not see play, only that it does not see play.

This is one of the many reasons that keep cards off of the points list. As more cards are added to the points list, more cards fall by the wayside. Decks only have 10 points to spend and certain options are more likely to be favored than others, leaving the remainder sitting in limbo with low play rates. It should be noted that a card being “unfun” is a poor argument to allow it to remain soft banned. Players approach this format with all kinds of play styles and find different cards fun or unfun, and as such, “fun” is a poor metric to use for keeping cards at a low play rate.

Drawback: Weakening a Deck Too Much

As a counterpoint to the “no free roll” benefit, sometimes pointing cards can lead to a deck becoming too weak. If a deck previously ran a card that has since become pointed, by definition, the deck has lost some power. If the deck chooses to keep the newly pointed card, the opportunity cost is found in the other pointed cards that the deck can no longer run. If the deck chooses to drop the newly pointed card, then they can no longer benefit from that card.

Psychic Frog, W&6, and M&B are powerful cards, but what happens if a deck wants all of them?

Consider the once popular Whiteless Control deck, commonly referred to as Czech Control or Czech Pile. This 4c deck was once considered one of the strongest and most resilient in the format and leaned on many multicolored cards as part of its threat suite and value engines. From October 2024 until the time of writing in June 2025, the deck has gained a minimum of 4 points (Psychic Frog, Wrenn and Six, M&B, Reanimate). All of these cards are exceptionally powerful on their own. It is not unreasonable to be willing to pay for Psychic Frog in the likes of UB Tempo, or to perhaps pay for M&B in Naya Monsters. However, when many cards overlap on the same deck, the opportunity costs compound. Adding newly pointed cards to a deck is usually not just additive, it is often exponential in terms of how much it affects the strength of the deck. Since then, Czech has dropped off dramatically in both play rate and viability.

While many of these changes were made with at least partial intent to reduce the strength of Czech Pile, it can probably be said that the deck was weakened too much. The opportunity cost of playing a different blue control deck is simply lower by moving to colors with fewer pointed cards. This is always a potential risk with adding more 1 point cards. Some decks lean very heavily on certain cards to remain viable, and while it is not possible for the format to support all decks equally, it is worth considering the damage that is done when pointing new cards. Sometimes, the price is acceptable, but other times the price is too high, and this is often a strong reason to be cautious when exploring new 1 point options.

Potential Drawback: Splash Damage

The final potential drawback that will be considered in this article is the concept of splash damage. The concept of splash damage comes from the idea of explosives: when an explosive goes off, it radiates damage all around it, not just at its target. When it comes to pointing cards, cards are often pointed with the intent to target a specific deck, but it is rare for a card to be played only in that deck. The other decks playing the card are splash damage; they were not the intended target but were hurt by the pointing nevertheless.

The reason splash damage is usually considered a drawback is that cards tend to be pointed for their use in the strongest decks, while weaker decks that incidentally play the card are made even weaker, further pushing them from viability. For example, the pointing of Merchant Scroll hurt the popular 3c and 4c Recall blue control decks who were flourishing at the top of the format, but it also hurt the 2c Recall blue control decks as well. Where a multicolored deck might have a lower opportunity cost to drop Merchant Scroll, such as the inclusion of Forth Eorlingas! in Jeskai, other decks like Blue Moon may face a harsher opportunity cost in order to keep up, as they may have been reliant on greater free access to Recall to make up for the lower average card quality present in 2c. This is an important consideration when deciding to point cards, as it is not ideal to remove weaker decks from the format unnecessarily. In an ideal world, the perfect pointing works with absolute precision and only hits the deck it is targeting; however, the world is far from ideal and this is rarely the case.

Splash damage is not always a drawback, and sometimes is quite intentional. Consider the previously mentioned example of the recent Balance pointing. Balance was used in everything from Time Vault to Reanimator to Omnitell to Storm. In this case, the fact that Balance hit all of these decks was purposeful to bring the overall power level of combo down. Splash damage can sometimes be used to great effect instead of multiple more surgical changes.

Conclusion

In conclusion, many of the points list decisions can be viewed through the lens of opportunity cost. While there are many potential benefits of 1-point cards, there are equally as many potential drawbacks to consider as well. This is part of what makes the points list so interesting and nuanced, but also so difficult to manage. This article is not comprehensive, but hopefully it provided some useful insights into pointing philosophy.

About the author:

Joshua Gottlieb is a Data Scientist and Canadian Highlander enthusiast who loves to dive into the theory of the format and brew many decks on Moxfield. Known on Discord as Cyclopes8, he is an active Tournament Organizer on the Discord server, mainly running Webcam events.

He also runs the CanlanderWinnersArchive Moxfield profile cataloguing winning lists from a wide variety of events, runs his own YouTube channel devoted to Canadian Highlander gameplay and theory, and is a member of the Discord Points Panel, a group whose purpose is to help connect the Candian Highlander council with the wider community.